Risky optimisation

AI risk viewed through the lens of optimisation.

Be careful how you specify your objectives.

Be careful how you specify your objectives.Comic by skeletonclaw, seen on the Princeton AI Safety course website.

Epistemic status: trying to convey an intuition. I’ll be oversimplifying complex systems for the sake of clarity. The goal is to convey a notion of “here is a shared quality of optimisation processes that makes me worry about the current AI trajectory”. This post assumes some prior knowledge of basic machine learning and also of AI risk, see for instance my previous blog post.

The law of the instrument states: “If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.” As a machine learning researcher in the deep learning era, the main tool I have is optimisation with stochastic gradient descent. As a result, everything looks like an optimisation landscape.1 We will see some examples of this later.

This perspective is a big part of my priors on the danger of building superhumanly capable AI. In other words, it informs my answer to the question: “If we build increasingly capable AI systems, do we get a good outcome by default or a bad outcome by default?”2

Optimisation, overfitting, regularisation

Fundamental to optimisation processes is that you need to specify an objective to optimise for. If you specify the objective wrong, the optimisation process does not care that you made a mistake; it just tries to optimise for the specified objective. If you want to optimise for human wellbeing, but you do not specify this correctly, you may not get what you want. There are many exampls of optimisation processes that may seem like they try to optimise for human wellbeing, but that – in actuality – optimise for something different. Evolution optimises for inclusive genetic fitness, not for happiness. Capitalism optimises for some notion of profits, not for human welfare.

Misspecified objectives can still correlate to what we want: evolution has given us an ability for experiencing happiness and wellbeing; capitalism has, on some axes, greatly increased human welfare; in machine learning, a low training loss can be indicative of good downstream performance. On the other hand, applying enough optimisation pressure to a particular metric will generally ruin the correlation between that metric and what you actually care about – Goodhart’s law3: runaway capitalism often destroys human welfare for the sake of profits; machine learning models overfit the training loss.

Objectives often encode the “spirit” of what we want, but the optimisation does not care about our intentions. Instead, it tries to achieve the “letter” of the objective that we specified; that is what it means for something to be an objective. By Goodhart’s law, these “letter” outcomes are attractor states in the optimisation landscape (or: the loss surface): they are usually what we get if we optimise hard enough. The obvious solution is making the “letter” coincide with the “spirit” somehow, but this is often unworkable. The actual thing we want to optimise for is generally hard to specify, because human values and society are both very complex systems. Choosing an easy-to-measure proxy to optimise instead only works when optimisation pressure is weak, because the “spirit” and “letter” of an objective quickly decorrelate, as stated by Goodhart’s law.

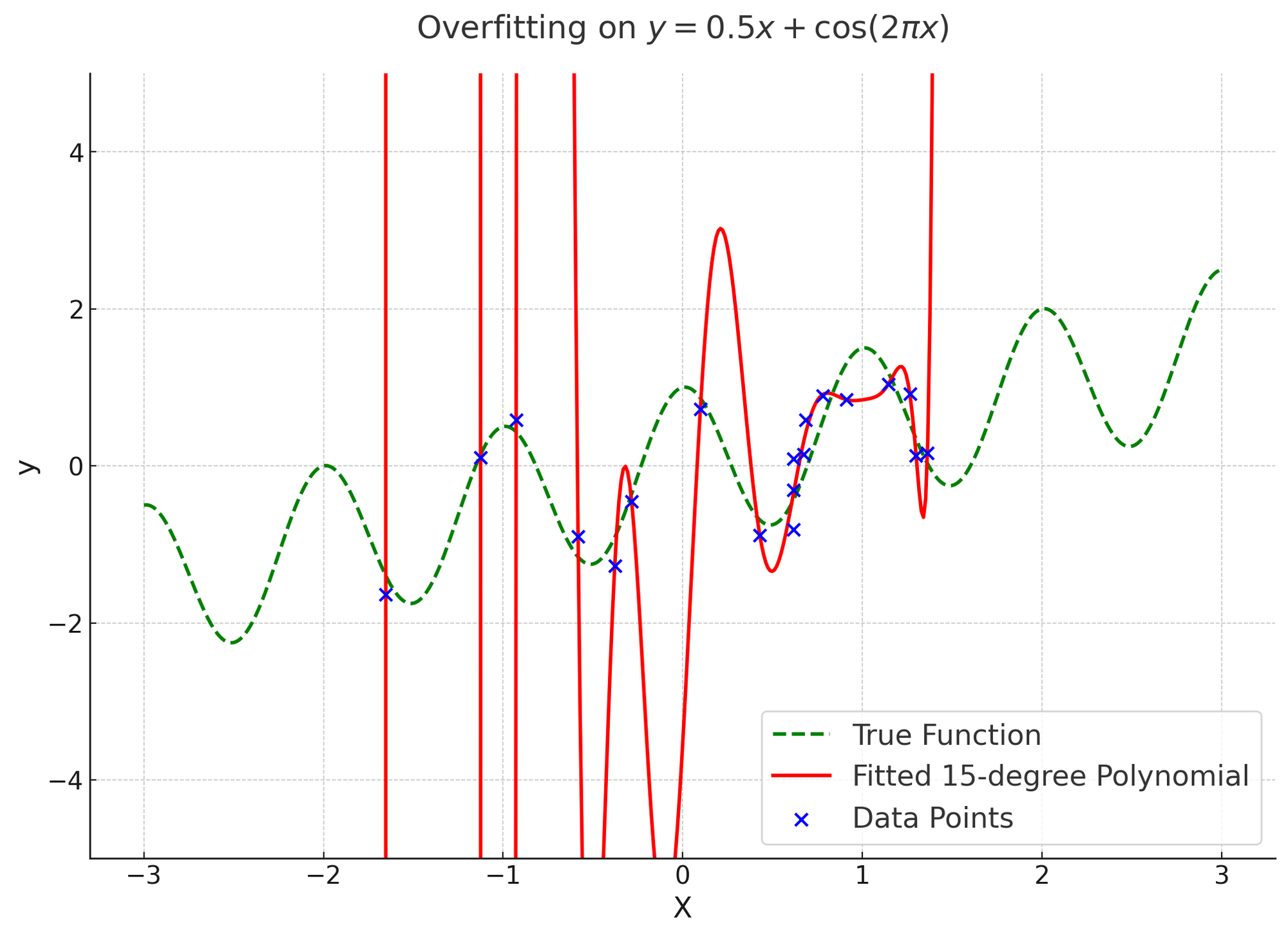

A case study: if you have any experience with machine learning, you are probably familiar with examples of overfitting like the image below4, where the learned fit takes ridiculous values for regions with no data. The “spirit” of this optimisation is to find a reasonable and predictive model of the data. The specified objective is to minimise the mean-squared error between a fitting function and the training data. The outcome that optimally satisfies the “letter” of the objective is to completely overfit the training data to achieve zero error.

To achieve this, the optimisation process sets “unimportant” parameters to extreme values. Here “unimportant” means anything not specified in the objective. Because the fitting function has more parameters than there are datapoints (the fit is heavily underdetermined), the optimisation algorithm is free to set some coefficients to pretty much whatever values it wants if that makes the remaining optimisation easier. The result is completely non-predictive function that heavily violates the “spirit” of the optimisation, but satisfies the “letter” better than any useful function ever could.5

This example generalises to societal optimisations. The absolute dystopian horror story that is factory farming is a very salient example of capitalism setting the “farmed animal welfare”-parameter to extremely negative values in the pursuit of profits. After all, ensuring animal welfare is expensive and makes the optimisation for profits harder. Other examples of this optimisation gone wrong are monopolies, centralisation of power, climate change, pollution, and increased inequality.

To fix this, we typically add regularisers: e.g., we change the objective function to remove such extremes. Preventing overfitting in the machine learning example may involve adding a weight-norm term to the loss function, or finding some other way of adding a simplicity prior to the optimisation process (e.g., choosing a better function class using our prior information). In societal optimisations, the regulariser is typically governance: antitrust laws, unions, climate accords, progressive tax systems, etc. None of this works remotely perfectly, but it mitigates some of the negative excesses of the optimisation process, avoiding some of the worst attractor states.

So what does all of this have to do with the current progress in AI? Quite a lot. I’m worried that AI may change the optimisation landscape of many processes, such that catastrophic outcomes become attractor states. The hope then is that we can use governance to regularise these optimisation processes away from bad outcomes. Things are not so simple, though: current governance solutions do not completely prevent bad outcomes even under the comparatively modest optimisation pressures in today’s – relatively AI-less – society. Simultaneously, optimisation pressures are bound to get stronger in the future as AI capabilities increase.

To make all this more concrete, let’s look at two societal processes that AI is very likely to impact: technology misuse and capitalism.

AI misuse

Individual people are, to some degree, optimisers with goals; at the very least we all want a variety of things and we work to change the world such that those things are more likely to happen. For some people, these goals are overall not in the best interest of other sentient beings. As a society, we generally try to make it hard to achieve such goals and disincentive the pursuit of those goals with the threat of social and institutional punishment. Such goals may range from scamming people, to destabilising societies, to simply blowing things up.6

Making achieving such goals easier is a bad idea, but AI tools may very well do this. E.g., what happens if everyone has a misinformation-bot at their fingertips? What happens if everyone has access to an open-source language model that can easily have its safeties stripped away / can be adversarially attacked to assist with executing biological attacks? What happens if everyone could have an agentic AI-assistant that competently executes instructions?

Another way of viewing this, is that AI tools potentially change the societal optimisation landscape to make the “minima” in which such bad-actor goals are achieved into attractor states. Many technologies are dual-use: they can be used for good and bad. The worst of these – e.g., bioweapons, nukes – are controlled by states, not individuals. That is a good thing: give everyone a nuke and we all get blown up; and let’s not forget all the close calls we have already experienced under the current limited state of nuclear proliferation. Mutual assured destruction (MAD) does not save you if some of the actors in your game theory are actually mad.

We live in a world where the damage that can be done by individuals is still limited, but – as Michael Nielsen puts it – how easy it is to find recipes for ruin is a question of physics. How certain are we that such recipes don’t exist, that AI systems cannot find them, or that we can stop bad-actors with AI assistance from implementing them?

We have experienced governance falling behind technology at an accelerated pace in the last few years, partially driven by developments in AI. By default, governance is likely to fall behind further. The result of weaker regulation is weaker regularisation on the societal optimisation process described above, with potentially disastrous outcomes. Luckily, it does seem that governance is actively trying to catch up: the EU AI Act, the UK AI Safety Summit, and the US Senate hearings on AI are positive signs.

AI-driven runaway capitalism

Let’s now zoom-out from individual actors to societal systems. Capitalism-as-an-optimisation-process optimises for profits (in the form of money) and is regularised by governance such that these profits remain somewhat correlated to the societal goal of human welfare: antitrust laws, unions, climate accords, and progressive tax systems are all examples of such regularising influences. AI risks destabilising this equilibrium in two ways: centralisation of power and value drift.

Centralisation of power

Just as increasingly capable AI can enable individuals to achieve previously unachievable goals, so can AI enable institutions. AI systems allow for efficient processing of large amounts of data, allowing institutions to take increasing advantage of economies of scale. Such centralisation of power leads to – among other things – near-monopolies, bad working conditions, and large scale tax-avoidance. Existing governance is still one factor in preventing the worst outcomes.7

OpenAI and DeepMind are explicitly aiming to build artificial general intelligence (AGI). So let’s imagine what might happen if they succeed at building artificial human-level strategic reasoners. Given that training current systems takes much more compute than running inference, it is likely that thousands or even millions of copies of such reasoners can be run in parallel: this is a huge strategic advantage over any merely-human competition. If the people who control such a system do not have cosmopolitan values and if governance is slow to catch up, this may lead to enormous power imbalances.

Open-source AI may be one road to mitigating these risks, but is not without the cost of heavily increasing misuse risks. We are currently seeing a race to AGI between OpenAI (backed by Microsoft), DeepMind (backed by Google) and Anthropic (backed by Amazon). Partially, this race is scary because it incentives trading safety for speed, thus increasing the technical risks of unaligned AI and the societal risks of ungoverned AI. But the race is also scary because it is unclear what happens if one of these companies succeeds at building AI aligned to their own goals.

Value drift and Goodhart dystopias

The second issue with AI-driven societal optimisation is value drift. Assuming AI ends up somewhat safe (initially) and no single institution obtains a decisive strategic advantage, we will be in a world where AI can be used to increase the efficiency of all kinds of processes.

This may initially seem like a good thing: more downstream profits, the economy may be doing well, and people may have access to all kinds of essential and novel products at lower costs than ever. Perhaps inequality will not be reduced as a consequence of a booming economy, but poverty likely will be, correlating with human welfare. In the simplest case, such an economic upturn may simply happen through automation of repetitive cognitive labour in select industries, but it is also feasible that AI systems will start automating software engineering or management work.

As AI systems become more and more capable, it is likely that we will embed them in all kinds of corporate and governmental systems. Perhaps there will be sufficient human oversight initially, but 1) this reduces efficiency and may be outcompeted by systems with less expensive oversight and 2) evaluating the downstream effects of decisions is very difficult and AI systems will likely seem to be doing a good job on the primary metrics, since that is what they would be trained for. This incentives yielding power to decision-making AI systems in the name of our optimisation process for human welfare as measured by the proxy of “economic indicators”.

Initially, this may seem fine, until Goodhart’s law sets in.8 More and more, AI may be integrated into society. More and more, people who refuse to use it may run into all kinds of societal barriers.9 More and more, the daily operation of society may be devoid of human influence, since the gradients of the optimisation process point into the direction of more and more efficiency and better economic indicators.

Finally, we may then realise that society no longer optimises for human welfare properly, as the cheap proxy of “economic indicators” has sufficiently decorrelated from welfare under the combined optimisation pressure of our AI-driven society. At this point, we may have already given away control to deeply embedded AI systems on which we are now fully dependent for our basic needs. Our societies’ values will have drifted to something not-quite human and we may have very little recourse to fix that: we have arrived at a “Goodhart dystopia”; a consequence of getting locked-in to Goodhart’s law.

AI takeover

I set out saying I am worried that AI may change the optimisation landscape of many processes, such that catastrophic outcomes become attraction states. In the example of AI misuse, the optimisation process was a human agent optimising for nefarious goals. For runaway capitalism, the optimisation process involved multiple coordinated processes optimising for local economic indicators. In both cases, the introduction of capable AI systems changed the trajectory of these optimisations to something more dangerous. But this is not the only risk: AI can also introduce novel dangerous optimisations.

Let’s explore this by adopting a frame from Andrew Critch’s fantastic post “What Multipolar Failure Looks Like, and Robust Agent-Agnostic Processes”. He starts out by telling a variation on the above Goodhart dystopia story, and notices there are two distinct ways of viewing the causes (taken from his blog post):

Agent-agnostic: humanity was destroyed because competitive pressures to increase production resulted in processes that gradually excluded humans from controlling the world, and eventually excluded humans from existing altogether. Agent-focused: humanity was destroyed by the aggregate behaviour of numerous agents, no one of which was primarily causally responsible, but each of which played a significant role.

This is a great illustration of viewing agents as a subset of optimisation processes. Note that the optimisation framework encompasses scenarios with and without agents: in evolution by natural selection, the optimisation process is not an agent at all. In the multi-agent scenario described above, the optimisation process is the result of many individual agents executing their individual optimisations. Our goal as a society in which optimisation processes are embedded, is to make sure we end up in a good place by guiding these processes through governance.10 Viewed this way, AI takeover scenarios are fairly natural outcomes of optimisation processes that are not sufficiently regularised.

The story above is not the only AI takeover scenario. There are more stories like this, and there are stories about single-agent takeovers. Of course, all of these are stylised to present a salient narrative, but the basic point is always the same: these potentially catastrophic consequences are the natural outcome of the way the optimisation process is set up.

In my previous blog post, I wrote at length about why technical AI alignment may be difficult, and how that could lead to takeovers as a consequence of instrumental convergence. Building agentic AI systems is an example of us potentially introducing a competing optimisation process into society, and reflects the same dangerous quality of optimisation: value is fragile; there are many more ways to break something than there are to improve it; Goodharting is everywhere; making the attractor state / default outcome good is hard and steering the optimisation away from bad outcomes is also hard as a result.

The technical problem is only part of the story: knowing how to make your optimiser do what you want is very important, but you also need to figure out how to prevent its existence from so drastically changing the current optimisation landscape that existing safeguards fail. These are not problems that are solved by default. Solving them requires that we closely govern AI developments: evals, red-teaming, accountability, compute governance, international cooperation, and many more developments may be necessary to mitigate the dangers. Of course, bad governance has its own risks: delaying life-saving innovations, security theatre leading to worse actual security (Goodhart’s law!), and – somewhat ironically – centralisation of power.

Closing

The upshot: optimisation is dangerous if it is not exactly your goals that are being optimised for. Humanity has not always been great at optimising for general human welfare11, but we do share a common evolutionary (and sometimes, cultural) history that encourages kindness, empathy, and mutual aid in certain situations. The fact that our current world is relatively pleasant for humans compared to many other sentients is the result of humans being the optimisers in charge.12 It seems prudent to be wary about introducing competing optimisers into this equilibrium.

This optimisation perspective is just one framework for thinking about AI risk, but it is one I find compelling and worrying. Of course, there are other frameworks as well, both those complementing and those contradicting specific predictions the optimisation perspective makes. Jacob Steinhardt discusses some of these in his blog series, which I definitely recommend as follow-up reading. The main insight that I have tried to convey in this piece is that many patterns both in society and in recent AI developments fit an optimisation lens, and that this lens expects worrying future outcomes by default.

Avoiding this default is both a technical and a governance problem, but likely more of the latter than of the former. Governance is actively trying to catch up, but – as threat models are not exactly clear – it is currently unknown which policies best mitigate the risks. If you want to know more about the various policy considerations, have a look at the AI Governance resources by the AI Safety Fundamentals team.

Perhaps this is better viewed as an example of a related concept named déformation professionnelle: a tendency to look at things from the point of view of one’s own profession. ↩︎

This is somewhat similar to what Jacob Steinhardt calls the optimisation anchor in his series of blog posts – which starts here, but read this one if you’ll read only one – on various methods for thinking about future AI developments. He argues that most ML researchers favour an engineering – “current ML” – anchor that aims to extrapolate from current trends and are more sceptical of thought-experiment type arguments. While he and I are both very partial to such an engineering mindset (it often works well!), he correctly identifies that it has a fundamental issue when thinking about future AI developments: we are seeing qualitative shifts in frontier model capabilities as a result of scaling (e.g., in-context learning, grokking, world models) and these phase shifts are becoming more and more common. Under the engineering mindset, extrapolating these trends implies that the engineering mindset will increasingly often give wrong predictions. Here the optimisation anchor can supplement the engineering anchor; for instance, the optimisation anchor would correctly predict imitative deception and power seeking for a wide variety of AI decision-making models. The primary difference between the perspective of my current blog post and Jacob’s optimisation anchor is that I view evolution and the economy as special cases of the optimisation anchor, while Jacob mentions them separately. ↩︎

This is all assuming we start out optimising for something remotely sensible to begin with. If you directly try to optimise for something terrible, you don’t need Goodhart’s law to know the outcome will not be good. ↩︎

Generated with ChatGPT. ↩︎

Why do overparameterised neural networks work? Partially, because they can satisfy the letter and spirit of the optimisation simultaneously. They can achieve both low train and test loss simultaneously, and seem to prefer generalising solutions that satisfy the spirit of the optimisation more than we would expect from a naive application of statistical learning theory. So why this preference for generalising solutions? One often cited reason is that stochastic gradient descent may have an implicit bias towards generalising solutions, and that this bias is responsible for neural network generalisation. But Loss Landscapes are All You Need (2023) shows that even training neural networks with random search tends to lead to generalising solutions. This instead suggests that overparameterisation leads to loss surfaces that have most of their low-training-loss volume in regions that correspond to generalising solutions, so that training will naturally tend to generalisation in this regime: a very different origin for the bias towards generalising solutions! This bias is a prediction of singular learning theory, a potential new candidate for explaining neural network generalisation, with potential applications for AI safety research in the form of developmental interpretability. ↩︎

These are primarily examples of instrumental goals, which operate in service of some more fundamental values. It may very well be that many such people would have much more cosmopolitan objectives if society were structurally more inclusive or kind, and working towards such a society seems like a great plan. However, given that we currently find ourselves in a society in which some people do have harmful-to-other-sentient-beings goals, it is a bad idea to enable them with helpful AI assistants. ↩︎

The Dutch East Indies Company is a great example of the kind of quasi-governmental power that corporations can potentially amass in the absence of current governance structures. It was “a powerful company, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, imprison and execute convicts, negotiate treaties, strike its own coins, and establish colonies.” ↩︎

Of course, this is a simplification. Probably there will already be many Goodhart-like consequences at earlier stages of the optimisation, just as we already see these consequences in the modern-day economy. The point is that trade-offs that initially seem worth it may be a reflection of a structure that will become a problem down the line, i.e., after applying more optimisation pressure. ↩︎

Just as there are now all kinds of societal barriers associated with not using the internet. ↩︎

Note that creating a society that can decently implement such governance is itself a (meta-)optimisation process of institutional design. ↩︎

This is also not entirely humanity’s fault: evolution has not given us a great set of starting conditions for a humane world: disease, resource scarcity, that whole thing with coming from a billions of years long optimisation process that mercilessly kills off anything not well-adapted to its environment (or that just happens to be unlucky) and that presumably finds intense suffering to be an efficient learning tool for avoiding behaviours that may get you mercilessly killed off and that does not even have the decency to shut that suffering off when the purpose is no longer served (e.g., wild animals being eaten alive). ↩︎

Both the fact that people need other people, and the fact that no-one in history was orders of magnitude better at optimising for their goals than the rest of the world was, helps keep things relatively stable. ↩︎